Gaussian Elimination¶

In this section we define some Python functions to help us solve linear systems in the most direct way. The algorithm is known as Gaussian Elimination, which we will simply refer to as elimination from this point forward. The idea of elimination is to exchange the system we are given with another system that has the same solution, but is much easier to solve. To this end we will perform a series of steps called row operations which preserve the solution of the system while gradually making the solution more accessible. There are three such operations we may perform.

Exchange the position of two equations.

Multiply an equation by any nonzero number.

Replace any equation with the sum of itself and a multiple of another equation.

Example 1: Row operations and elimination¶

Let’s look at an example.

We could swap the first and last equation,

or we could multiply the first equation by \(5\),

or we could add 2 times the first equation to the last equation.

The last operation is the most important because it allows us to eliminate a variable from one of the equations. Note that the third equation no longer contains the \(x_2\) term. This is the key to the elimination algorithm.

For computational purposes we can dispense with the variable names and the “=” symbol, and arrange all of the actual numbers in an array.

Now let’s build a NumPy array with these values. We’ll assign the array the name \(\texttt{A}\), so that we can refer to it later.

import numpy as np

A=np.array([[1,-1,1,3],[2,1,8,18],[4,2,-3,-2]])

We could dive in an start performing operations on our array, but instead we will first write a few bits of code that will do each of these operations individually. We will tuck each operation inside a Python function so that we can use it again for future calculations.

def RowSwap(A,k,l):

# =============================================================================

# A is a NumPy array. RowSwap will return duplicate array with rows

# k and l swapped.

# =============================================================================

m = A.shape[0] # m is number of rows in A

n = A.shape[1] # n is number of columns in A

B = np.copy(A).astype('float64')

for j in range(n):

temp = B[k][j]

B[k][j] = B[l][j]

B[l][j] = temp

return B

def RowScale(A,k,scale):

# =============================================================================

# A is a NumPy array. RowScale will return duplicate array with the

# entries of row k multiplied by scale.

# =============================================================================

m = A.shape[0] # m is number of rows in A

n = A.shape[1] # n is number of columns in A

B = np.copy(A).astype('float64')

for j in range(n):

B[k][j] *= scale

return B

def RowAdd(A,k,l,scale):

# =============================================================================

# A is a numpy array. RowAdd will return duplicate array with row

# l modifed. The new values will be the old values of row l added to

# the values of row k, multiplied by scale.

# =============================================================================

m = A.shape[0] # m is number of rows in A

n = A.shape[1] # n is number of columns in A

B = np.copy(A).astype('float64')

for j in range(n):

B[l][j] += B[k][j]*scale

return B

We now have three new functions called \(\texttt{RowSwap}\),\(\texttt{RowScale}\),and \(\texttt{RowAdd}\). Let’s try them out to see what they produce.

B1 = RowSwap(A,0,2)

B2 = RowScale(A,2,0.5)

B3 = RowAdd(A,0,1,2)

print(A)

print('\n')

print(B2)

[[ 1 -1 1 3]

[ 2 1 8 18]

[ 4 2 -3 -2]]

[[ 1. -1. 1. 3. ]

[ 2. 1. 8. 18. ]

[ 2. 1. -1.5 -1. ]]

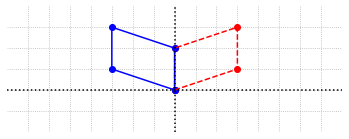

The goal of elimination is to perform row operations on this array in order to produce a new array with a structure that looks something like this.

(Note that the * symbols here represent different unknown values that may or may not be 0 or 1.)

We will carry out the row operations and save our progress as arrays with new names after each step. For example, we might name them \(\texttt{A1}\), \(\texttt{A2}\), \(\texttt{A3}\), etc. This way we can check the progress, or go back and make changes to our code if we like.

## Add -2 times row 0 to row 1

A1 = RowAdd(A,0,1,-2)

print(A1,'\n')

## Add -4 times row 0 to row 2

A2 = RowAdd(A1,0,2,-4)

print(A2,'\n')

## Add -2 times row 1 to row 2

A3 = RowAdd(A2,1,2,-2)

print(A3,'\n')

## Multiply row 1 by 1/3

A4 = RowScale(A3,1,1.0/3)

print(A4,'\n')

## Multiply row 2 by 1/19

A5 = RowScale(A4,2,1.0/-19.)

print(A5)

[[ 1. -1. 1. 3.]

[ 0. 3. 6. 12.]

[ 4. 2. -3. -2.]]

[[ 1. -1. 1. 3.]

[ 0. 3. 6. 12.]

[ 0. 6. -7. -14.]]

[[ 1. -1. 1. 3.]

[ 0. 3. 6. 12.]

[ 0. 0. -19. -38.]]

[[ 1. -1. 1. 3.]

[ 0. 1. 2. 4.]

[ 0. 0. -19. -38.]]

[[ 1. -1. 1. 3.]

[ 0. 1. 2. 4.]

[-0. -0. 1. 2.]]

Now let’s translate this array back to the description of the system with all the symbols in place.

After the steps of elimination, we have what is known as a upper triangular system. The solution to this system can be found without much effort by working backwards from the last equation. The last equation tells us that \(x_3 = 2\). If we substitute that value into the second equation, we find that \(x_2 = 0\). Finally, if we substitute these values back into the first equation, we find that \(x_1 = 1.\) This process for finding the solution of the upper triangular system is called back substitution.

Example 2: Elimination on a random array¶

If a system of equations has a solution, the elimination algorithm will always result in a upper triangular system that can be solved by back substitution. In this next example, we look at the calculation with a small change to see it in a more general way. This time when we use the \(\texttt{RowAdd}\) function, we will set the scale parameter based on the values in the array.

To help us avoid writing the code based on the entries in any specific matrix, we will make up a matrix of random numbers using the \(\texttt{random}\) module.

R = np.random.randint(-8,8,size=(3,4))

print(R)

[[-7 1 5 -1]

[-2 -4 4 5]

[ 3 4 1 -1]]

## Scale the first row based on the first element in that row.

R1 = RowScale(R,0,1.0/R[0][0])

## Add the first row to the second based on the first element in the second row.

R2 = RowAdd(R1,0,1,-R[1][0])

## Add the first row to the last based on the first element in the last row.

R3 = RowAdd(R2,0,2,-R2[2][0])

## Scale the second row based on the second element in that row.

R4 = RowScale(R3,1,1.0/R3[1][1])

## Add the second row to the last based on the second element in the last row.

R5 = RowAdd(R4,1,2,-R4[2][1])

## Scale the last row based on the last element in that row.

R6 = RowScale(R5,2,1.0/R5[2][2])

print(R6)

[[ 1. -0.14285714 -0.71428571 0.14285714]

[-0. 1. -0.6 -1.23333333]

[ 0. 0. 1. 0.6954023 ]]

Once we understand how the row operations work, and we are sure that they are working correctly, we might not have any reason to store the results of the intermediate steps of elimination. In that case, we could simplify the code considerably by resusing the same array name for each step. The following code would produce the same result, but we would no longer have access to the original array, or any of the intermediate steps.

R = RowScale(R,0,1.0/R[0][0])

R = RowAdd(R,0,1,-R[1][0])

R = RowAdd(R,0,2,-R[2][0])

R = RowScale(R,1,1.0/R[1][1])

R = RowAdd(R,1,2,-R[2][1])

R = RowScale(R,2,1.0/R[2][2])

print(R)

Execute the code in this example several times. Each time array \(\texttt{R}\) is created it will be populated with random integers between -8 and 8. Does the code always produce a upper triangular system ready for back substitution? See if you can figure out which part of the process might fail, and why?

Example 3: Finding pivots¶

As we can see, the code in the last example fails if a zero shows up as any of the entries in the array that we divide by in order to calculate the scale factors. These critical entries are known as the pivots, and their locations in the matrix are called pivot positions. By definition, pivots must be nonzero. If a zero arises in a pivot position during the elimination steps, we can try to exchange the order of the rows to move a nonzero entry into the pivot position. Let’s first try this for a specific array before trying to write code that will work for a random array.

G=np.array([[1,-1,1,3],[2,-2,4,8],[3,0,-9,0]])

print(G)

[[ 1 -1 1 3]

[ 2 -2 4 8]

[ 3 0 -9 0]]

## Add -2 times row 0 to row 1

G1 = RowAdd(G,0,1,-2)

## Add -3 times row 0 to row 2

G2 = RowAdd(G1,0,2,-3)

print(G2)

[[ 1. -1. 1. 3.]

[ 0. 0. 2. 2.]

[ 0. 3. -12. -9.]]

Now there is a zero in the middle pivot position. We can swap the middle and last equation in order to carry on the elimination.

## Swap rows 1 and 2

G3 = RowSwap(G2,1,2)

## Scale the new row 1 by 1/3

G4 = RowScale(G3,1,1./3)

## Scale the new row 2 by 1/2

G5 = RowScale(G4,2,1./2)

print(G5)

[[ 1. -1. 1. 3.]

[ 0. 1. -4. -3.]

[ 0. 0. 1. 1.]]

We write the system again as a familar set of equations.

Applying back substitution, we find that \(x_2 = 1\) and \(x_1=3\).

It is worth noting that the swapping of rows is only necessary as a matter of organization. Here is another way that we could have done the elimination and ended up with a system that is just the same.

## Scale row 1 by 1/2

G3_alternative = RowScale(G2,1,1./2)

## Scale row 2 by 1/3

G4_alternative = RowScale(G3_alternative,2,1./3)

print(G4_alternative)

[[ 1. -1. 1. 3.]

[ 0. 0. 1. 1.]

[ 0. 1. -4. -3.]]

The array produced represents the same simplified system, with the equations in a different order of course.

The idea of back substitution works just as well with this form of the system, but the organization of the algorithm becomes slightly more complicated.

Example 4: Elimination fails¶

Let’s make a small change to the system in the previous example and observe an example of how the elimination process can break down.

H = np.array([[1,-1,1,3],[2,-2,4,8],[3,-3,-9,0]])

print(H)

[[ 1 -1 1 3]

[ 2 -2 4 8]

[ 3 -3 -9 0]]

## Add -2 times row 0 to row 1

H1 = RowAdd(H,0,1,-2)

## Add -3 times row 0 to row 2

H2 = RowAdd(H1,0,2,-3)

print(H2)

[[ 1. -1. 1. 3.]

[ 0. 0. 2. 2.]

[ 0. 0. -12. -9.]]

In this case exchanging the second and third rows does not help since both rows have a zero in the middle entry. This means that there is no pivot in the second column. Let’s scale the rows and look at the result.

## Multiply row 1 by 1/2

H3 = RowScale(H2,1,1./2)

## Multiply row 2 by -1/12

H4 = RowScale(H3,2,-1./12)

print(H4)

[[ 1. -1. 1. 3. ]

[ 0. 0. 1. 1. ]

[-0. -0. 1. 0.75]]

When we write out the equations, we see that this system is inconsistent. The last two equations contradict each other.

Note that we did not make any errors in the calculation and that there is no way to reorder the equations to alleviate the problem. This system simply does not have a solution. We will revisit this scenario in future sections and provide a characterization for such systems.

Example 5: Nonunique solution¶

In this final example of elimination, we observe another possible outcome of the process.

F = np.array([[1,-1,1,3],[2,-2,4,8],[1,-1,3,5]])

print(F)

[[ 1 -1 1 3]

[ 2 -2 4 8]

[ 1 -1 3 5]]

## Add -2 times row 0 to row 1

F1 = RowAdd(F,0,1,-2)

## Add -3 times row 0 to row 2

F2 = RowAdd(F1,0,2,-1)

print(F2)

[[ 1. -1. 1. 3.]

[ 0. 0. 2. 2.]

[ 0. 0. 2. 2.]]

Similar to the previous example, we see that there is no way to bring a nonzero number into the second column of the second row. In this case though we see that the second and third equations do not contradict each other, but are in fact the same equation.

Let’s do just two more row operations to simplify this system even further.

## Add -1 times row 1 to row 2

F3 = RowAdd(F2,1,2,-1)

## Multiply row 1 by 1/2

F4 = RowScale(F3,1,0.5)

print(F4)

[[ 1. -1. 1. 3.]

[ 0. 0. 1. 1.]

[ 0. 0. 0. 0.]]

Since the final equation is true for any values of \(x_1\), \(x_2\), \(x_3\), we see that there are really only two equations to determine the values of the three unknowns.

Since the middle equation tells us that \(x_3=1\), we can plug that value into the first equation using the idea of back substitution. This leaves us with the single equation \(x_1-x_2 = 2\). This equation, and thus the system as a whole, has an infinite number of solutions. We will revist this idea and provide further details in the next chapter.

Exercises¶

Exercise 1: In the system below, use a row operation functions to produce a zero coefficient in the location of the coefficient 12. Do this first by hand and then create a NumPy array to represent the system and use the row operation functions. (There are two ways to create the zero using \(\texttt{RowAdd}\). Try to find both.)

## Code solution here.

Exercise 2: Create a NumPy array to represent the system below. Determine which coefficient should be zero in order for the system to be upper triangular. Use \(\texttt{RowAdd}\) to carry out the row operation and then print your results.

## Code solution here.

Exercise 3: Carry out the elimination process on the following system. Define a NumPy array and make use of the row operation functions. Print the results of each step. Write down the upper triangular system represented by the array after all steps are completed.

# Code solution here

Exercise 4: Use row operations on the system below to produce an lower triangular system. The first equation of the lower triangular system should contain only \(x_1\) and the second equation should contain only \(x_1\) and \(x_2\).

# Code solution here

Exercise 5: Use elimination to determine whether the following system is consistent or inconsistent.

# Code solution here

Exercise 6: Use elimination to show that this system of equations has no solution.

# Code solution here

Exercise 7: Use \(\texttt{random}\) module to produce a \(3\times 4\) array which contains random integers between \(0\) and \(5\). Write code that performs a row operation to produce a matrix with a zero in the first row, third column. Run the code several times to be sure that it works on different random arrays. Will the code ever fail?

# Code solution here

Exercise 8: Starting from the array that represents the upper triangular system in Example 1 (\(\texttt{A5}\)), use the row operations to produce an array of the following form. Do one step at a time and again print your results to check that you are successful.

## Code solution here.

Exercise 9: Redo Example 2 using the \(\texttt{random}\) module to produce a \(3\times 4\) array made up of random floats instead of random integers.

## Code solution here.

Exercise 10: Write a loop that will execute the elimination code in Example 2 on 1000 different \(3\times 4\) arrays of random floats to see how frequently it fails.

## Code solution here.