Inverse Matrices¶

In this section we consider the idea of inverse matrices and describe a common method for their construction.

As a motivation for the idea, let’s again consider the system of linear equations written in the matrix form.

Again, \(A\) is a matrix of coefficients that are known, \(B\) is a vector of known data, and \(X\) is a vector that is unknown. If \(A\), \(B\), and \(X\) were instead only numbers, we would recognize immediately that the way to solve for \(X\) is to divide both sides of the equation by \(A\), so long as \(A\neq 0\). The natural question to ask about the system is Can we define matrix division?

The answer is Not quite. We can make progress though by understanding that in the case that \(A\),\(B\), and \(X\) are numbers, we could also find the solution by multiplying by \(1/A\). This subtle distinction is important because it means that we do not need to define division. We only need to find the number, that when multiplied by \(A\) gives 1. This number is called the multiplicative inverse of \(A\) and is written as \(1/A\), so long as \(A\neq 0\).

We can extend this idea to the situation where \(A\), \(B\), and \(X\) are matrices. In order to solve the system \(AX=B\), we want to multiply by a certain matrix, that when multiplied by \(A\) will give the identity matrix \(I\). This matrix is known as the inverse matrix, and is given the symbol \(A^{-1}\).

If \(A\) is a square matrix we define \(A^{-1}\) (read as “A inverse”) to be the matrix such that the following are true.

Notes about inverse matrices:

The matrix must be square in order for this definition to make sense. If \(A\) is not square, it is impossible for both \(A^{-1}A\) and \(AA^{-1}\) to be defined.

Not all matrices have inverses. Matrices that do have inverses are called invertible matrices. Matrices that do not have inverses are called non-invertible, or singular, matrices.

If a matrix is invertible, its inverse is unique.

Now if we know \(A^{-1}\), we can solve the system \(AX=B\) by multiplying both sides by \(A^{-1}\).

Then \(A^{-1}AX = IX = X\), so the solution to the system is \(X=A^{-1}B\). Unfortunately, it is typically not easy to find \(A^{-1}\).

Construction of an inverse matrix¶

We take \(C\) as an example matrix, and consider how we might build the inverse.

Let’s think of the matrix product \(CC^{-1}= I\) in terms of the columns of \(C^{-1}\). We put focus on the third column as an example, and label those unknown entries with \(y_i\). The * entries are uknown as well, but we will ignore them for the moment.

Recall now that \(C\) multiplied by the third column of \(C^{-1}\) produces the third column of \(I\). This gives us a linear system to solve for the \(y_i\).

import numpy as np

import laguide as lag

## Solve CY = I3

C = np.array([[1,0,2,-1],[3,1,-3,2],[2,0,4,4],[2,1,-1,-1]])

I3 = np.array([[0],[0],[1],[0]])

Y3 = lag.SolveSystem(C,I3)

print(Y3)

[[-0.16666667]

[ 0.66666667]

[ 0.16666667]

[ 0.16666667]]

The other columns of \(C^{-1}\) can be found by solving similar systems with the corresponding columns of the identity matrix. We can then build \(C^{-1}\) by assembling the columns into a single matrix, and test the result by checking the products \(C^{-1}C\) and \(CC^{-1}\).

I1 = np.array([[1],[0],[0],[0]])

I2 = np.array([[0],[1],[0],[0]])

I4 = np.array([[0],[0],[0],[1]])

Y1 = lag.SolveSystem(C,I1)

Y2 = lag.SolveSystem(C,I2)

Y4 = lag.SolveSystem(C,I4)

C_inverse = np.hstack((Y1,Y2,Y3,Y4))

print("C inverse:\n",C_inverse,'\n',sep='')

print("C inverse times C:\n",C_inverse@C,'\n',sep='')

print("C times C inverse:\n",C@C_inverse,sep='')

C inverse:

[[ 0.83333333 0.5 -0.16666667 -0.5 ]

[-2.08333333 -1.25 0.66666667 2.25 ]

[-0.08333333 -0.25 0.16666667 0.25 ]

[-0.33333333 0. 0.16666667 0. ]]

C inverse times C:

[[ 1.00000000e+00 0.00000000e+00 -1.11022302e-16 0.00000000e+00]

[ 0.00000000e+00 1.00000000e+00 0.00000000e+00 0.00000000e+00]

[ 0.00000000e+00 0.00000000e+00 1.00000000e+00 0.00000000e+00]

[ 0.00000000e+00 0.00000000e+00 0.00000000e+00 1.00000000e+00]]

C times C inverse:

[[ 1.00000000e+00 0.00000000e+00 0.00000000e+00 0.00000000e+00]

[ 0.00000000e+00 1.00000000e+00 0.00000000e+00 0.00000000e+00]

[ 0.00000000e+00 0.00000000e+00 1.00000000e+00 0.00000000e+00]

[-4.44089210e-16 0.00000000e+00 1.11022302e-16 1.00000000e+00]]

Similar to the situation in the previous section, some of the entries that should be zero are not exactly zero due to roundoff error. Again, we can display a rounded version to read the results more easily.

print(np.round(C@C_inverse,8))

[[ 1. 0. 0. 0.]

[ 0. 1. 0. 0.]

[ 0. 0. 1. 0.]

[-0. 0. 0. 1.]]

We will next write a Python function to compute the inverse of a matrix. In practice finding the inverse of a matrix is a terribly inefficient way of solving a linear system. We have to solve \(n\) systems to just to find the inverse of an \(n \times n\) matrix, so it appears that it takes \(n\) times the amount of work that it would to just solve the system by elimination. Suppose however that we needed to solve a linear system \(AX=B\) for many different vectors \(B\), but the same coefficient matrix \(A\). In that case it might seem appealing to construct \(A^{-1}\).

In order to keep the computation somewhat efficient, we want to avoid repeating the row operations as much as possible. In order to construct \(A^{-1}\) we need to solve the system \(AX_i=Y_i\), where \(Y_i\) is the \(i\)th column of \(I\). This will produce \(X\), which is the \(i\)th column of \(A^{-1}\). Instead of performing elimination on each augmented matrix \([A|Y_i]\), we can augment \(A\) with the entire matrix \(I\) and perform the required operations on all \(Y_i\) at the same time. For example, if \(A\) is a \(4\times 4\) matrix, we will have the following augmented matrix.

If \(A\) is invertible, the \(\texttt{RowReduction}\) routine from the previous section should return a matrix of the following form.

We can then call the \(\texttt{BackSubstitution}\) function once for each column in the right half of this matrix.

def Inverse(A):

# =============================================================================

# A is a NumPy array that represents a matrix of dimension n x n.

# Inverse computes the inverse matrix by solving AX=I where I is the identity.

# If A is not invertible, Inverse will not return correct results.

# =============================================================================

# Check shape of A

if (A.shape[0] != A.shape[1]):

print("Inverse accepts only square arrays.")

return

n = A.shape[0] # n is number of rows and columns in A

I = np.eye(n)

# The augmented matrix is A together with all the columns of I. RowReduction is

# carried out simultaneously for all n systems.

A_augmented = np.hstack((A,I))

R = lag.RowReduction(A_augmented)

Inverse = np.zeros((n,n))

# Now BackSubstitution is carried out for each column and the result is stored

# in the corresponding column of Inverse.

A_reduced = R[:,0:n]

for i in range(0,n):

B_reduced = R[:,n+i:n+i+1]

Inverse[:,i:i+1] = lag.BackSubstitution(A_reduced,B_reduced)

return(Inverse)

print(Inverse(C))

[[ 0.83333333 0.5 -0.16666667 -0.5 ]

[-2.08333333 -1.25 0.66666667 2.25 ]

[-0.08333333 -0.25 0.16666667 0.25 ]

[-0.33333333 0. 0.16666667 0. ]]

If a matrix is non-invertible then the process above fails. We have to realize that within the \(\texttt{BackSubstitution}\) routine we divide by the entries along the main diagonal of the upper triangular matrix. Recall that these entries are in the very important pivot positions. If there is a zero in at least one pivot position, then the original matrix is non-invertible.

Suppose for example that after performing \(\texttt{RowReduction}\) on the augmented matrix \([A|I]\) in the \(\texttt{Inverse}\) routine, the result is as follows.

In this case \( \texttt {BackSubstitution}\) will fail due to the zero in the pivot position of the second row. Hence, \(A^{-1}\) does not exist and we can conclude that \(A\) is non-invertible.

In general we determine if a given matrix is invertible by carrying out the steps of elimination and examining the entries on the main diagonal of the corresponding upper triangular matrix. The original matrix is invertible if and only if all of those entries are nonzoro.

One-sided inverses¶

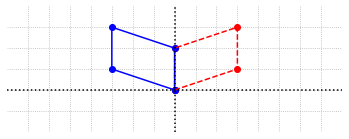

When a matrix is not square it cannot be considered invertible by the definition above. It can be useful however to consider one-sided inverses. If \(A\) is an \(m\times n\) matrix, we say that a matrix \(F\) is a right inverse of \(A\) if \(AF=I_m\). Similarly, we say that a matrix \(G\) is a left inverse of \(A\) if \(GA=I_n\). Note here that both the right inverse \(F\) and the left inverse \(G\) are \(n\times m\) matrices, \(I_m\) is the \(m\times m\) identity matrix, and \(I_n\) is the \(n\times n\) identity matrix.

It is interesting to note that if a matrix \(A\) has both a right inverse \(F\) and a left inverse \(G\) then they must be equal since

This means that unless \(A\) is square (with \(m=n\)) it cannot have both a left inverse and a right inverse.

The one-sided inverses are also related to the solution of the linear system \(AX=B\). If \(A\) has a right inverse \(F\) then the system must have at least one solution, \(X = FB\).

We shall see later that the system \(AX=B\) has at most one solution when \(A\) has a left inverse.

Inverse matrices with SciPy¶

The \(\texttt{inv}\) function is used to compute inverse matrices in the SciPy \(\texttt{linalg}\) module. Once the module is imported, the usage of \(\texttt{inv}\) is exactly the same as the function we just created.

import scipy.linalg as sla

C_inverse = sla.inv(C)

print(C_inverse)

[[ 0.83333333 0.5 -0.16666667 -0.5 ]

[-2.08333333 -1.25 0.66666667 2.25 ]

[-0.08333333 -0.25 0.16666667 0.25 ]

[-0.33333333 0. 0.16666667 0. ]]

Providing a non-invertible matrix to \(\texttt{inv}\) will result in an error being raised by the Python interpreter.

Exercises¶

Exercise 1: Solve the following system of equations using an inverse matrix.

## Code solution here

Exercise 2: Let \(A\) and \(B\) be two random \(4\times 4\) matrices. Demonstrate using Python that \((AB)^{-1}=B^{-1}A^{-1}\) for the matrices.

## Code solution here

Exercise 3: Explain why \((AB)^{-1}=B^{-1}A^{-1}\) by using the definition given in this section.

Exercise 4: Solve the system \(AX=B\) by finding \(A^{-1}\) and computing \(X=A^{-1}B\).

## Code solution here

Exercise 5: Find a \(3 \times 3 \) matrix \(Y\) such that \(AY = C\).

## Code solution here

Exercise 6: Let \(A\) be a random \(4 \times 1\) matrix and \(B\) is a random \( 1 \times 4 \) matrix. Use Python to demonstrate that the product \( AB \) is not invertible. Do you expect this to be true for any two matrices \(P\) and \(Q\) such that \(P\) is an \( n \times 1 \) matrix and \(Q\) is a \( 1 \times n\) matrix ? Explain.

## Code solution here

Exercise 7: Let \(A\) be a random \( 3 \times 3\) matrices. Demonstrate using Python that \((A^T)^{-1} = (A^{-1})^T\) for the matrix. Use this property to explain why \(A^{-1}\) must be symmetric if \(A\) is symmetric.

## Code solution here

Exercise 8: Consider the following \( 4 \times 4 \) matrix:

\((a)\) Find the condition on \(x_1\), \(x_2\), \(x_3\) or \(x_4\) for which \(A^{-1}\) exists. Assuming that condition is true, find the inverse of \(A\).

\((b)\) Use Python to check if \( A^{-1}A = I \) when \(x_1 = 4\), \(x_2 = 1\), \(x_3 = 1\), and \(x_4 = 3\).

## Code solution here

Exercise 9: Apply the methods used in this section to compute a right inverse of the matrix \(A\).

## Code solution here