Orthogonal Subspaces¶

In this section we extend the notion of orthogonality from pairs of vectors to whole vector subspaces. If \(\mathcal{V}\) and \(\mathcal{W}\) are subspaces of \(\mathbb{R}^n\), we say that \(\mathcal{V}\) and \(\mathcal{W}\) are orthogonal subspaces if every vector in \(\mathcal{V}\) is orthogonal to every vector in \(\mathcal{W}\).

As an example, let’s suppose that \(E_1\), \(E_2\), \(E_3\), and \(E_4\) are the standard basis vectors for \(\mathbb{R}^4\)

Now let’s suppose \(\mathcal{V}\) is the span of \(\{E_1, E_2\}\), and \(\mathcal{W}\) is the span of \(\{E_4\}\). Arbitrary vectors \(V\) in \(\mathcal{V}\) and \(W\) in \(\mathcal{W}\) have the following forms, and clearly \(V\cdot W = 0\), for any values of \(a\), \(b\) and \(c\).

A closely related idea is that of orthogonal complements. If \(\mathcal{V}\) is a subspace of \(\mathbb{R}^n\), the orthogonal complement of \(\mathcal{V}\) is the set of all vectors in \(\mathbb{R}^n\) that are orthogonal to \(\mathcal{V}\). The orthogonal complement of \(\mathcal{V}\) is also a subspace of \(\mathbb{R}^n\) and is given the symbol \(\mathcal{V}^{\perp}\).

In the previous example, the orthogonal complement of \(\mathcal{V}\) is the span of \(\{E_3, E_4\}\) and the orthogonal complement of \(\mathcal{W}\) is the span of \(\{E_1, E_2, E_3\}\).

If the bases elements are not standard, we can determine if \(\mathcal{V}\) and \(\mathcal{W}\) are orthogonal, or orthogonal complements in \(\mathbb{R}^n\), by examining the elements of their bases. If \(\alpha\) is a basis for \(\mathcal{V}\) and \(\beta\) is a basis for \(\mathcal{W}\), then \(\mathcal{V}\) and \(\mathcal{W}\) are orthogonal if every vector in \(\alpha\) is orthogonal to every vector in \(\beta\). If every vector in \(\alpha\) is orthogonal to every vector in \(\beta\) and the combined set of vectors in \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) forms a basis for \(\mathbb{R}^n\), then \(\mathcal{V}\) and \(\mathcal{W}\) are orthogonal complements in \(\mathbb{R}^n\).

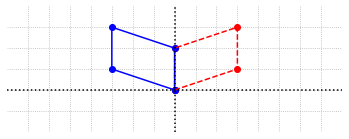

Example 1: Orthogonal subspaces¶

Let \(\mathcal{V}\) be the span of \(\{V_1\}\) and \(\mathcal{W}\) be the span of \(\{W_1\}\).

In order to verify that \(\mathcal{V}\) and \(\mathcal{W}\) are orthogonal subspaces, we have to show that any arbitrary vector in \(\mathcal{V}\) is orthogonal to any arbitrary vector in \(\mathcal{W}\). In this example, the subspaces are really just orthogonal lines in \(\mathbb{R}^3\). Any vector \(V\) in \(\mathcal{V}\) can be written as \(V=aV_1\) for some scalar \(a\), and any vector \(W\) in \(\mathcal{W}\) can be written as \(W=bW_1\) for some scalar \(b\). Then by the properties of the dot product we have \(V\cdot W = (aV_1)\cdot(bW_1) = ab(V_1\cdot W_1) = 0\). This shows that \(\mathcal{V}\) and \(\mathcal{W}\) are orthogonal subspaces.

The two spaces \(\mathcal{V}\) and \(\mathcal{W}\) in this example are not orthogonal complements since \(\{V_1, W_1\}\) do not form a basis for \(\mathbb{R}^3\). Any basis for \(\mathbb{R}^3\) must contain exactly three vectors.

Example 2: Orthogonal complements¶

Let \(\alpha = \{V_1, V_2\}\) be a basis for \(\mathcal{V}\) and \(\beta = \{W_1, W_2\}\) be a basis for \(\mathcal{W}\), and suppose that we wish to determine if \(\mathcal{V}\) and \(\mathcal{W}\) are orthogonal complements in \(\mathbb{R}^4\).

To determine if \(\mathcal{V}\) and \(\mathcal{W}\) are orthogonal subspaces, we need to check that each vector in \(\alpha\) is orthogonal to each vector in \(\beta\). A convenient way to do this is to assemble matrices \(A\) and \(B\) with these vectors as columns and then compute \(A^TB\).

import numpy as np

V=np.array([[2, 2],[1, 3],[1, -1],[0, 4]])

print(V,'\n')

W=np.array([[-1, 1],[0, -4],[2, 2],[1, 3]])

print(W,'\n')

print(V.transpose()@W)

[[ 2 2]

[ 1 3]

[ 1 -1]

[ 0 4]]

[[-1 1]

[ 0 -4]

[ 2 2]

[ 1 3]]

[[0 0]

[0 0]]

Since \(A^TB\) is the zero matrix, it means that \(V_i\cdot W_j=0\) for all pairs of values \(i,j\). To understand why this implies that every vector in \(\mathcal{V}\) is orthogonal to every vector in \(\mathcal{W}\), we can express arbitrary vectors in these spaces in terms of the basis elements. If \(V\) and \(W\) are arbitrary vectors in \(\mathcal{V}\) and \(\mathcal{W}\) respectively, then \(V=a_1V_1 + a_2V_2\) and \(W=b_1W_1 + b_2W_2\). We can then use the properties of the dot product to show that \(V\cdot W =0\).

Now that we know \(\mathcal{V}\) and \(\mathcal{W}\) are orthogonal subspaces, we want to check that they are also orthogonal complements. To do this, we need to determine if \(\{V_1, V_2, W_1, W_2\}\) form a basis for \(\mathbb{R}^4\). Recall that if the set is a basis, the vector equation \(B=c_1V_1 + c_2V_2 +c_3W_1 + c_4W_4\) has a unique solution for any vector \(B\) in \(\mathbb{R}^4\). To see if this is indeed true, we can assemble a matrix \(A\) with these vectors as columns, and examine the pivot positions revealed by the RREF.

import laguide as lag

A = np.hstack((V,W))

print(A,'\n')

print(lag.RowReduction(A))

[[ 2 2 -1 1]

[ 1 3 0 -4]

[ 1 -1 2 2]

[ 0 4 1 3]]

[[ 1. 1. -0.5 0.5 ]

[ 0. 1. 0.25 -2.25]

[ 0. 0. 1. -1. ]

[ 0. 0. 0. 1. ]]

The presence of a pivot in each row and column indicates that \(B=c_1V_1 + c_2V_2 +c_3W_1 + c_4W_4\) has a unique solution for every \(B\) in \(\mathbb{R}^4\), which means that \(\{V_1, V_2, W_1, W_2\}\) is a basis for \(\mathbb{R}^4\). Together with the fact that \(\mathcal{V}\) and \(\mathcal{W}\) are orthogonal, we can conclude that \(\mathcal{W} = \mathcal{V}^{\perp}\).

Orthogonal decomposition¶

The previous example reveals an important property of orthogonal complements. If we are given orthogonal complements \(\mathcal{V}\) and \(\mathcal{V}^{\perp}\) for \(\mathbb{R}^n\), then every vector \(X\) in \(\mathbb{R}^n\) can be written as the sum of two components, one in \(\mathcal{V}\), and the other in \(\mathcal{V}^{\perp}\). This idea parallels that of projecting one vector onto another. Any \(X\) in \(\mathbb{R}^n\) can be written as \(X = P + E\) where \(P\) is the projection of \(X\) onto the subspace \(\mathcal{V}\), and \(E\) is in \(\mathcal{V}^{\perp}\). Since the complements are orthogonal, we know that \(P\cdot E = 0\).

In order to compute the the projection of a vector \(X\) onto a subspace \(\mathcal{V}\), we use of an orthonormal basis \(\{U_1,U_2,U_3,..., U_n\}\) for \(\mathcal{V}\). The projection \(P\) is the sum of projections onto the individual basis vectors.

It is important to note that if the given basis for \(\mathcal{V}\) is not orthonormal, we must first use the Gram-Schimdt algorithm to generate an orthonormal basis in order to make use of this formula.

Fundamental subspaces¶

In Chapter 2 we defined the column space and the null space of a matrix, and asserted that there are four fundamental subspaces associated with every matrix. In this section, we define the other two subspaces, and observe that they are the orthogonal complements of the first two spaces.

If \(A\) is an \(m\times n\) matrix, the row space of \(A\) is defined as the span of the rows of \(A\). Alternatively, we could say that the row space of \(A\) is the column space of \(A^T\). The row space of \(A\) is a subspace of \(\mathbb{R}^n\), and is the orthogonal complement of \(\mathcal{N}(A)\), the null space of \(A\). Recall that a vector \(X\) is in \(\mathcal{N}(A)\) if \(AX=0\). The entries of the vector \(AX\) are exactly the values of the dot products of \(X\) with each of the rows of \(A\). Since these entries are all zero, \(X\) is orthogonal to each row of \(A\).

The left null space of an \(m\times n\) matrix \(A\) is the orthogonal complement of \(\mathcal{C}(A)\), the column space of \(A\) in \(\mathbb{R}^m\). Since the column space of \(A\) is also the row space of \(A^T\), it must also be that the orthogonal complement of the column space is the null space of \(A^T\).

Example 3: Demonstrating orthogonality of fundamental subspaces¶

Let’s demonstrate the orthogonality of the row space and null space for a specific matrix. We will construct a basis for each of the subspaces so that we can apply the same reasoning as in the previous example.

To find a basis for \(\mathcal{N}(A)\) we need to solve \(AX=0\).

A = np.array([[2, 1, 2, 0],[3, 0, 1, 1],[1, 1, 1, 0]])

A_reduced = lag.FullRowReduction(A)

print(A_reduced)

[[ 1. 0. 0. 0.5]

[ 0. 1. 0. 0. ]

[ 0. 0. 1. -0.5]]

The RREF tells us that \(AX=0\) implies \(x_1 = -0.5x_4\), \(x_2=0\), and \(x_3 = 0.5x_4\). This means that any vector in \(\mathcal{N}(A)\) has the following form.

We can see by multiplication with \(A\) that a vector of this form is orthogonal to each row, and thus any vector in the row space. Because there is a pivot in each row of \(A\), we know that the rows, if viewed as vectors, are linearly independent. Alternatively, we could check that there is a pivot in each column of \(A^T\).

print(lag.FullRowReduction(A.transpose()))

[[1. 0. 0.]

[0. 1. 0.]

[0. 0. 1.]

[0. 0. 0.]]

We have shown that \(\mathcal{N}(A)\), the null space of \(A\), and \(\mathcal{C}(A^T)\), the row space of \(A\) form orthogonal complements in \(\mathbb{R}^4\), and have the following bases.

Note that we can find bases for the column space and left null space by applying the same process to \(A^T\). The calculation is left as an exercise.

Exercises¶

Exercise 1: Let \(B\) be the following \(4\times 3\) matrix. Find bases for \(\mathcal{C}(B^T)\) and \(\mathcal{N}(B)\), the row space and null space of \(B\).

## Code solution here.

Exercise 2: Using the matrix \(B\) and the bases from the previous exercise, determine vectors \(P\) and \(E\) such that \(P\) is in \(\mathcal{C}(B^T)\), \(E\) is in \(\mathcal{N}(B)\), and \(P+E = X\), where \(X\) is the following vector.

## Code solution here.

Exercise 3: Let \(A\) be the matrix in Example 3. Find bases for \(\mathcal{C}(A)\) and \(\mathcal{N}(A^T)\), the column space and left null space of \(A\).

A = np.array([[2, 1, 2, 0],[3, 0, 1, 1],[1, 1, 1, 0]])

## Code solution here.

Exercise 4: Let \(\mathcal{U}\) be the subspace of \(\mathbb{R}^4\) spanned by \(\{U_1,U_2\}\). Find a basis for the orthogonal complement \(U^{\perp}\).

## Code solution here.

Exercise 5: Let \(\mathcal{W}\) be the subspace of \(\mathbb{R}^5\) spanned by \(\{W_1, W_2, W_3\}\). Find a basis for the orthogonal complement \(\mathcal{W}^{\perp}\).

## Code solution here.

Exercise 6: Let \(U\) and \(W\) be the subspaces of \(\mathbb{R}^4\) where \(U\) is the span of \(\{V_1,V_2\}\) and \(W\) is the span of \(\{V_3,V_4\}\). Determine whether \(U\) and \(W\) are orthogonal complements of each other.

## Code solution here

Exercise 7: Find vectors \(P\) and \(E\) such that \(P\) is in the column space of the matrix \(A\), \(E\) is orthogonal to \(P\) and \(B = P + E\). Verify your answer.

## Code solution here

Exercise 8: Let \(\{X_1,X_2\}\) be a basis for subspace \(U\) of \(\mathbb{R}^3\) and \(\{X_3\}\) be a basis for \(W\). Find the values of \(a\) and \(b\) for which subspaces \(U\) are \(W\) are orthogonal complements of each other.

## Code solution here

Exercise 9: Let \(U\) be a subspace of \(\mathbb{R}^4\) and it has \(3\) vectors in its basis. Can you determine the number of vectors in the basis of \(U^{\perp}\)?

## Code solution here

Exercise 10: Let \(U\) of \(\mathbb{R}^3\) spanned by \(\{X_1,X_2\}\). Decompose the vector \(V\) in \(\mathbb{R}^3\) such that one component is in subspace \(U\) and other component in \(U^{\perp}\).

## Code solution here

Exercise 11:

(\(a\)) Find a basis for each of the four of fundamental subspaces (\(\mathcal{C}(A)\), \(\mathcal{N}(A)\), \(\mathcal{R}(A)\), and \(\mathcal{N}(A^T)\)) associated with \(A\).

## Code solution here.

\((b)\) Show that each vector in the basis of the row space \(\mathcal{R}(A)\) is orthogonal to each vector in the basis of the null space \(\mathcal{N}(A)\).

## Code solution here.

\((c)\) Show that each vector in the basis of the column space \(\mathcal{C}(A)\) is orthogonal to each vector in the basis of the left nullspace \(\mathcal{N}(A^T)\).

## Code solution here.

Exercise 12: The equation \(x + 2y - 3z = 0\) defines a plane in \(\mathbb{R}^3\).

\((a)\) Find a matrix that has this plane as its null space. Is the matrix unique?

## Code solution here.

\((b)\) Find a matrix that has this plane as its row space. Is the matrix unique?

## Code solution here.