Matrix Representations¶

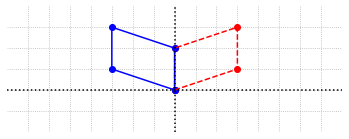

A key connection between linear transformations and matrix algebra is the fact that every linear transformation can be carried out by matrix multiplication. It is natural then to associate the matrix with the linear transformation in some way. Conversely, when carrying out matrix multiplication, it is quite natural to consider the associated linear transformation that it represents. In this way, matrix multiplication can be viewed as a means of mapping vectors in one space to vectors in another.

Instead of tackling the most general case of finding matrix representations, let’s consider a linear transformation from \(\mathbb{R}^n\) to \(\mathbb{R}^m\). The defining properties of linear transformations imply that it can be described just be specifying the images (output) of each element in a basis for \(\mathbb{R}^n\). Suppose that \(T\) is our transformation, \(\beta = \{V_1, V_2,..., V_n\}\) is a basis for \(\mathbb{R}^n\), and we know the images \(T(V_1)\), \(T(V_2)\), …, \(T(V_n)\). This is the only information we need to work out \(T(X)\) for an arbitrary \(X\) in \(\mathbb{R}^n\). First we express \(X\) in terms of the basis, \(X = c_1V_1 + c_2V_2 + ... c_nV_n\), then use the linearity of the transformation.

In order to make the connection to matrices, we must recognize that the right-hand side of this equation can be expressed as a matrix-vector multiplication. The columns of the matrix are the images of the basis vectors, and the vector is the coordinate vector of \(X\) with respect to the basis \(\beta\).

The matrix that represents the linear transformation thus depends on the basis that we choose to describe \(\mathbb{R}^n\), which means that each choice of basis will give a different matrix. In this section, we will restrict our attention to matrix representations associated with the standard basis.

Standard matrix representations¶

When we choose the standard basis \(\alpha = \{E_1, E_2, ..., E_n\}\) for \(\mathbb{R}^n\), we will refer to the matrix representation of a linear transformation as the standard matrix representation. We introduce a slightly different notation for this matrix, even though it is just an ordinary matrix like all the others we have used in previous chapters. If we use \(T\) as the label for our transformation, we will use the notation \(\left[T\right]\) to represent the standard matrix representation of \(T\).

Example 1: Transformation from \(\mathbb{R}^2\) to \(\mathbb{R}^4\)¶

Consider the transformation \(T:\mathbb{R}^2\to\mathbb{R}^4\), with the following images defined.

The standard matrix representation is built using these images as columns.

Now if \(X\) is some other vector in \(\mathbb{R}^2\), we can compute \(T(X)\) as the matrix-vector product \(\left[T\right]X\).

Example 2: Transformation from \(\mathbb{R}^3\) to \(\mathbb{R}^3\)¶

A linear transformation \(L:\mathbb{R}^3 \to \mathbb{R}^3\) could be defined with a formula such as the following.

In order to find the standard matrix representation of \(L\), we first apply the formula to produce the images of the standard basis, and then assemble them to form \(\left[L\right]\)

Analysis using RREF¶

Now that we are able to represent a linear transformation as a matrix-vector multiplication, we can use what we learned in the previous chapter to determine if linear transformations are invertible. Suppose the transformation \(T:\mathbb{R}^n \to \mathbb{R}^m\) has the standard matrix representation \([T]\), and we want to know if there exists an inverse transformation \(T^{-1}:\mathbb{R}^m \to \mathbb{R}^n\). We need to know if the linear system \([T]X = B\) has a unique soluition for every \(B\) in \(\mathbb{R}^m\).

Looking back to the discussion in General Linear Systems we see that the system \([T]X = B\) is inconsistent if the augmented matrix associated with this system has a pivot in the last column. The only way that this is possible is if the matrix \([T]\) has a row with no pivot, since there can be no more than one pivot per row. We also found that \([T]X=B\) will have a unique solution when there is a pivot in each column of \([T]\). Thus \([T]X=B\) will have a unique solution for every \(B\) in \(\mathbb{R}^m\) exactly when the matrix \([T]\) has a pivot in each row and in each column. In this case the linear transformation \(T\) will be invertible, and the matrix \([T]\) will have an inverse.

There are two other properties of linear transformations that are very closely related to these.

In the case that the linear system \([T]X=B\) has at least one solution for every \(B\) in \(\mathbb{R}^m\), the transformation is said to be onto \(\mathbb{R}^m\). In this case, for every vector \(B\) in \(\mathbb{R}^m\), there is at least one vector \(X\) in \(\mathbb{R}^n\) so that \(T(X)=B\). The transformation \(T\) is onto whenever the matrix \([T]\) has a pivot in every row.

In the case that the linear system \([T]X=B\) has at most one solution for every \(B\) in \(\mathbb{R}^m\), the linear transformation is said to be one-to-one. In this case, no two vectors in \(\mathbb{R}^n\) get sent to the same vector in \(\mathbb{R}^m\). The transformation \(T\) is one-to-one whenever the matrix \([T]\) has a pivot in every column.

A transformation is invertible if and only if it is both onto and one-to-one.

If we keep in mind that there can be at most one pivot per column and one pivot per row, we can make a further statement about these properties based on the relative size of \(m\) and \(n\). If \(T:\mathbb{R}^n\to\mathbb{R}^m\), then \(T\) cannot be onto \(\mathbb{R}^m\) if \(m>n\), and cannot be one-to-one if \(m<n\). Only when \(m=n\) is it possible for \(T\) to be invertible.

Let’s look at our examples. In Example 1, the matrix \([T]\) is \(4\times 2\). We know the matrix can have at most two pivots (at most one per column), so it cannot have a pivot in each row. To see if there are pivots in each column, we can compute the RREF.

import numpy as np

import laguide as lag

T = np.array([[2, 0],[0,1],[1, -1],[1,4]])

print(lag.FullRowReduction(T))

[[1. 0.]

[0. 1.]

[0. 0.]

[0. 0.]]

In this case, the transformation \(T\) is one-to-one, but is not onto.

In Example 2 the matrix \([L]\) is \(3\times3\) and we need to to compute the RREF to determine the pivot locations.

L=np.array([[1,0,-1],[3,-1,2],[2,8,0]])

print(lag.FullRowReduction(L))

[[1. 0. 0.]

[0. 1. 0.]

[0. 0. 1.]]

Since the matrix representation has a pivot in each row and column, the transformation \(L\) is invertible.

Exercises¶

Exercise 1: For each of the following linear transformations, find the standard matrix representation, and then determine if the transformation is onto, one-to-one, or invertible.

(\(a\))

## Code solution here.

(\(b\))

## Code solution here.

Exercise 2: Let \(L:\mathbb{R}^3 \to \mathbb{R}^2\) be the linear transformation defined by \(L(X)= AX\).

Determine whether \(L:\mathbb{R}^3 \to \mathbb{R}^2\) is an invertible transformation or not.

## Code solution here.

Exercise 3: \(L:\mathbb{R}^3\to\mathbb{R}^2\) is a Linear Transformation. Find \(L(X)\) given the following vectors.

## Code solution here

Exercise 4: The standard matrix representation of a linear transformation \(S\) is given below. Determine the input and output space of \(S\) by looking at the dimensions of \(\left[S\right]\). Determine whether \(S\) is an invertible transformation.

## Code solution here

Exercise 5: The linear transformation \(W:\mathbb{R}^3\to\mathbb{R}^3\) is an invertible transformation. Find \(X\).

## Code solution here

Exercise 6: Let \(T:\mathbb{R}^3\to\mathbb{R}^3\) be a linear transformation. Given that there are two vectors in \(\mathbb{R}^3\) which get mapped to the same vector in \(\mathbb{R}^3\), what can you say about the number of solutions for \([T]X=B\)? Explain why \(T\) is not an invertible transformation.