QR Factorization¶

In Chapter 1 we saw that the LU factorization essentially captured the elimination process and stored the result in a way that allowed us to use elimination to solve similar systems without having to carry out the elimination again. The QR factorization accomplishes something similar for the orthogonalization process. Given a matrix \(A\) with linearly independent columns, the QR factorization of \(A\) is a pair of matrices \(Q\) and \(R\) such that \(Q\) is orthogonal, \(R\) is upper triangular, and \(QR=A\).

Structure of orthogonalization¶

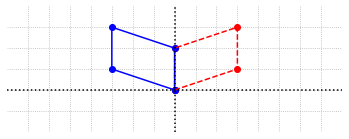

If \(A\) is an \(m\times n\) matrix with linearly independent columns, it must be that \(m \ge n\). The matrix \(Q\) then will be \(m\times n\) with orthonormal columns, and \(R\) will be \(n\times n\) and upper triangular. For example, if \(A\) is a \(6\times 4\) matrix, the matrices have the following structures, with the \(A_i\) and \(U_i\) being vectors in \(\mathbb{R}^6\).

The columns of \(Q\) are the result of applying the orthogonalization process to the columns of \(A\). If we suppose that this is the case, let’s explain why \(R\) must be triangular by looking at the product \(QR\) one column at a time. For the first column we have the following vector equation which specifies the linear combination of the \(U\) vectors that form \(A_1\).

We know however that \(U_1\) is the unit vector in the direction of \(A_1\). This means that \(r_{21}=r_{31}=r_{41}=0\) and \(r_{11} = |A_1|\). Let’s also note that \(|A_1| = U_1\cdot A_1\).

For the second column we have a similar equation.

We know from the orthogonalization process that \(U_2\) is built by subtracting from \(A_2\) the component that is in the \(U_1\) direction. Thus, \(A_2\) is a linear combination of \(U_1\) and \(U_2\). This means that \(r_{32}=r_{42}=0\) and \(r_{12}\) and \(r_{22}\) are the coordinates of \(A_2\) with respect to \(U_1\) and \(U_2\), which we can compute as \(r_{12} = U_1\cdot A_2\) and \(r_{22} = U_2\cdot A_2\).

Carrying out the same reasoning for the last two columns, we find that in general \(r_{ij} = U_i\cdot A_j\) and that \(r_{ij} = 0\) for \(i>j\) because the span of \(\{U_1, U_2, ..., U_i\}\) is equal to the span of \(\{A_1, A_2, ..., A_i\}\).

To arrive at this conclusion this more succinctly, we could multiply the equation \(A=QR\) by \(Q^T\), which gives \(Q^TA=Q^TQR\) and \(Q^TA = R\) since \(Q^TQ = I\). If we then understand the matrix product \(Q^TA\) as a collection of dot products between rows of \(Q^T\) and columns of \(A\), we have again that \(r_{ij} = U_i \cdot A_j\).

Example 1: Finding a QR factorization¶

Let’s compute the QR factorization for a specific \(6\times 4 \) matrix.

import numpy as np

from laguide import DotProduct as Dot

from laguide import Magnitude

# Define A

A = np.array([[1, 3, 2, 0], [0, -1, -1, 0], [2, 2, 1, 1], [-1, 1, 3, 4],[-4, 0, 1, -2],[0, -1, -2, 5]])

# Slice out the columns of A for processing

A_1 = A[:,0:1]

A_2 = A[:,1:2]

A_3 = A[:,2:3]

A_4 = A[:,3:4]

# Carry out Gram-Schmidt process

U_1 = A_1/Magnitude(A_1)

W_2 = A_2 - Dot(A_2,U_1)*U_1

U_2 = W_2/Magnitude(W_2)

W_3 = A_3 - Dot(A_3,U_1)*U_1 - Dot(A_3,U_2)*U_2

U_3 = W_3/Magnitude(W_3)

W_4 = A_4 - Dot(A_4,U_1)*U_1 - Dot(A_4,U_2)*U_2 - Dot(A_4,U_3)*U_3

U_4 = W_4/Magnitude(W_4)

# Assemble the matrix Q

Q = np.hstack((U_1,U_2,U_3,U_4))

print("Q")

print(Q,'\n')

# Check that Q is orthogonal

print("QTQ")

print(np.round(Q.transpose()@Q),'\n')

# Compute R

R = Q.transpose()@A

# Check

print("Q")

print(Q,'\n')

print("R")

print(np.round(R,8),'\n')

print("QR")

print(np.round(Q@R))

Q

[[ 0.21320072 0.71960864 -0.32643805 0.03625532]

[ 0. -0.2638565 0.01525411 -0.00954087]

[ 0.42640143 0.38379127 -0.10982963 0.09922508]

[-0.21320072 0.33581737 0.74745161 0.52474801]

[-0.85280287 0.28784346 -0.32338723 -0.07251063]

[ 0. -0.2638565 -0.46677591 0.84150499]]

QTQ

[[ 1. 0. -0. 0.]

[ 0. 1. -0. 0.]

[-0. -0. 1. 0.]

[ 0. 0. 0. 1.]]

Q

[[ 0.21320072 0.71960864 -0.32643805 0.03625532]

[ 0. -0.2638565 0.01525411 -0.00954087]

[ 0.42640143 0.38379127 -0.10982963 0.09922508]

[-0.21320072 0.33581737 0.74745161 0.52474801]

[-0.85280287 0.28784346 -0.32338723 -0.07251063]

[ 0. -0.2638565 -0.46677591 0.84150499]]

R

[[ 4.69041576 1.2792043 -0.63960215 1.2792043 ]

[ 0. 3.78993883 3.90987361 -0.16790868]

[-0. -0. 2.07455958 1.19287176]

[ 0. 0. 0. 6.55076331]]

QR

[[ 1. 3. 2. -0.]

[-0. -1. -1. -0.]

[ 2. 2. 1. 1.]

[-1. 1. 3. 4.]

[-4. 0. 1. -2.]

[ 0. -1. -2. 5.]]

QR factorization function¶

It is helpful to write some code in a more general way so that we may easily carry out the factorization on an arbitrary matrix with linearly independent columns. We will include in our function a simple check of the dimensions of the input matrix. If the number of columns is greater than the number of rows, the columns cannot be linearly independent since the number of columns exceeds the dimension of the column space. If this is the case, we will return an error message and not carry out any computations. If the number of columns is not greater than the number of rows, we will leave it to the user of the function to check that the columns are linearly independent. We can document this requirement with a comment in the code.

def QRFactorization(A):

# =============================================================================

# A is a Numpy array that represents a matrix of dimension m x n.

# QRFactorization returns matrices Q and R such that A=QR, Q is orthogonal

# and R is upper triangular. The factorization is carried out using classical

# Gram-Schmidt and the results may suffer due to numerical instability.

# QRFactorization may not return correct results if the columns of A are

# linearly dependent.

# =============================================================================

# Check shape of A

if (A.shape[0] < A.shape[1]):

print("A must have more rows than columns for QR factorization.")

return

m = A.shape[0]

n = A.shape[1]

Q = np.zeros((m,n))

R = np.zeros((n,n))

for i in range(n):

W = A[:,i:i+1]

for j in range(i):

W = W - Dot(A[:,i:i+1],Q[:,j:j+1])*Q[:,j:j+1]

Q[:,i:i+1] = W/Magnitude(W)

R = Q.transpose()@A

return (Q,R)

One point to note here is that our function returns the pair of matrices \(Q\) and \(R\). In order to receive both results, we need to assign a pair of names to the output. This is exactly the same behavior as the SciPy function we used in Chapter 1 to compute the PLU factorization.

Q,R = QRFactorization(A)

print(Q)

print('\n')

print(np.round(R,8))

[[ 0.21320072 0.71960864 -0.32643805 0.03625532]

[ 0. -0.2638565 0.01525411 -0.00954087]

[ 0.42640143 0.38379127 -0.10982963 0.09922508]

[-0.21320072 0.33581737 0.74745161 0.52474801]

[-0.85280287 0.28784346 -0.32338723 -0.07251063]

[ 0. -0.2638565 -0.46677591 0.84150499]]

[[ 4.69041576 1.2792043 -0.63960215 1.2792043 ]

[ 0. 3.78993883 3.90987361 -0.16790868]

[-0. -0. 2.07455958 1.19287176]

[ 0. 0. 0. 6.55076331]]

Example 2: Solving a linear system¶

The orthogonalization behind the \(QR\) factorization provides us another way to solve a linear system \(AX=B\). If we substitute \(A=QR\), then multiply the equation by \(Q^T\), we get \(Q^TQRX = Q^TB\). Once again \(Q^TQ\) simplifies to \(I\), so we are left with \(RX=Q^TB\), which is a triangular system that can be solved easily by back substitution.

Let’s try it out on a \(4\times 4\) system.

from laguide import BackSubstitution

A = np.array([[2, 3, 0, -1],[-1, 0, 2, 0],[-1, -1, 4, 2],[0, 3, -3, 2]])

B = np.array([[0],[1],[2],[5]])

X = np.array([[-1],[1],[0],[1]])

Q,R = QRFactorization(A)

C = Q.transpose()@B

X = BackSubstitution(R,C)

print(np.around(X,8),'\n')

## Check that AX = B

print(np.around(A@X,8))

[[-1.]

[ 1.]

[-0.]

[ 1.]]

[[0.]

[1.]

[2.]

[5.]]

In some situations, we might find that we are solving several systems such as \(AX=B_1\), \(AX=B_2\), \(AX=B_3\), …, that involve the same matrix but different right hand sides. In these situations it is useful to solve the systems with a factorization such as \(QR\) or \(LU\), because the factorization does not need to be recomputed for each system.

QR factorization with SciPy¶

The SciPy function for finding \(QR\) factorizations is called \(\texttt{qr}\). The basic use is exactly the same as our \(\texttt{QRfactorization}\) function. We apply \(\texttt{qr}\) to the matrix in the example and compare the results with our own computations.

import scipy.linalg as sla

Qs,Rs = sla.qr(A)

print("laguid Q\n",Q,'\n',sep='')

print("SciPy Q\n",Qs,'\n',sep='')

print("laguide R\n",np.around(R,8),'\n',sep='')

print("SciPy R\n",Rs,sep='')

laguid Q

[[ 0.81649658 0.20254787 0.53410762 -0.08388532]

[-0.40824829 0.35445878 0.37110075 -0.75496791]

[-0.40824829 0.05063697 0.69711449 0.58719726]

[ 0. 0.91146543 -0.30173612 0.27961774]]

SciPy Q

[[-0.81649658 -0.20254787 -0.53410762 -0.08388532]

[ 0.40824829 -0.35445878 -0.37110075 -0.75496791]

[ 0.40824829 -0.05063697 -0.69711449 0.58719726]

[-0. -0.91146543 0.30173612 0.27961774]]

laguide R

[[ 2.44948974 2.85773803 -2.44948974 -1.63299316]

[-0. 3.29140294 -1.82293086 1.72165692]

[ 0. -0. 4.43586779 0.25664911]

[ 0. 0. -0. 1.81751534]]

SciPy R

[[-2.44948974 -2.85773803 2.44948974 1.63299316]

[ 0. -3.29140294 1.82293086 -1.72165692]

[ 0. 0. -4.43586779 -0.25664911]

[ 0. 0. 0. 1.81751534]]

Although the results are displayed are close, we note that the entries of the SciPy are the negative of those we produced. The SciPy function does not actually use the Gram Schmidt process, but instead approaches the factorization from an entirely different direction.

Exercises¶

Exercise 1:

(\(a\)) Carry out the Gram-Schmidt algorithm on the following set of vectors to produce an orthonormal set \(\{U_1, U_2, U_3\}\). Do not use the \(\texttt{QRFactorization}\) function from this section or the SciPy \(\texttt{qr}\) function.

## Code solution here.

(\(b\)) Check your results by verifying that \(\{U_1, U_2, U_3\}\) is an orthonormal set and that the span of \(\{U_1, U_2, U_3\}\) equals the span of \(\{V_1, V_2, V_3\}\). (Reread Linear_Combinations if you are unsure how to verify the two spans are equal.)

## Code solution here.

(\(c\)) Check your results against those obtained using the \(\texttt{QRFactorization}\) function from this section or the \(\texttt{qr}\) function from SciPy.

## Code solution here.

Exercise 2:

(\(a\)) Predict what will happen if we attempt to find the QR factorization of matrix with linearly dependent columns.

(\(b\)) Try to compute the QR factorization on the following matrix with linearly dependent columns. Try both the \(\texttt{QRFactorization}\) function from this section or the \(\texttt{qr}\) function from SciPy.

## Code solution here.

Exercise 3: If possible, find the \(QR\) factorization of the matrix \(A\). Try to find the matrices \(Q\) and \(R\) without using the \(\texttt{QRFactorization}\) function from this section, then check your result by verifying that \(QR=A\).

## Code solution here

Exercise 4: Are all matrices which have \(QR\) factorization invertible? Explain.

## Code solution here

Exercise 5: Use the \(QR\) factorization of \(A\) to solve the given linear system \(AX = B\), and verify the solution.

## Code solution here

Exercise 6: \(A\) and \(B\) are two \(n \times n\) matrices.

(\(a\)) Given that the product \(BA\) has \(QR\) factorization, prove that the matrix \(A\) also has a \(QR\) factorization.

(\(b\)) Can you think of matrices \(A\) and \(B\) such that \(B\) has linearly dependent columns but the product \(BA\) has \(QR\) factorization? Explain.

## Code solution here

Exercise 7: If \(A\) is an \(n \times n\) invertible matrix, explain why \(A^TA\) is also invertible.